Google Hire, AI and the Privacy Paradox

In the recently released 2018 edition of her seminal annual Internet Trends report, Kleiner Perkins partner Mary Meeker recently discussed what she referred to as the ‘privacy paradox.’

She describes this phenomenon as the fact that while internet companies are “making low priced services better, in part, from user data,” and while internet users are “increasing time on internet services based on perceived value,” that same user data constitutes something of a devil’s bargain – essentially, in order to utilize platforms such as Facebook, or LinkedIn, or even Uber, users must essentially exchange their personal privacy in exchange for what amounts to, more or less, convenience and ease of use.

As Meeker notes, there is a growing amount of legislation, regulations and consumer safeguards currently being implemented in order to protect the personal data and privacy of internet users from the services who collect and monetize this information, whether that’s through behavioral targeting or selling that data to third party services (the most notorious example of which, Cambridge Analytica, is likely the best example of Meeker’s ‘privacy paradox’ in action).

While Meeker seems to embrace a more robust online regulatory environment around personal data, her report also suggests that such regulation could have the potential to harm innovation – hence another privacy paradox, wherein company growth and industry innovation could potentially be stifled by too many consumer protections and legislative constraints.

Of course, most of these consumer protections and privacy regulations continue to regulate internet users outside of the United States, particularly in the European Union. With last month’s sweeping GDPR rules coming into effect to “harmonize data privacy laws across Europe,” according to the European Commission, individual nations have also acted accordingly.

For example, Argentina first adopted rules regarding the ‘right to be forgotten’ (similar legislation has since been adopted by the European Commission, South Korea, and India, among other countries) in 2006. After a dozen years, this legislation, described in Article 43 of the Argentine “Habeas Data” code (gotta love that Latin), still seems progressive for much of the world, promises, “

“Any person shall file this action to obtain information on the data about himself and their purpose, registered in public records or databases, or in private ones intended to supply information; and in case of false data or discrimination, this action may be filed to request the suppression, rectification, confidentiality or updating of said data.”

In other words, Argentine internet users are able to correct, delete or update any personal information about them that exists online; otherwise, that consumer data is required to remain confidential, with significant associated penalties. Similarly, in Canada, data privacy is codified by legislation as a basic human right, much like the ability to speak French or put gravy and cheese curds on fries.

One developed country, of course, lags far behind all others when it comes to protecting online privacy and user confidentiality: the good old US of A, where we’re able to carry an AR 15 around as a Constitutional safeguard of our personal freedoms, but internet companies can do damned well whatever they please when it comes to your personal information.

As the cliché goes, freedom isn’t free, which is basically the business model of most every Silicon Valley based startup when it comes to personal information – and if you’re an American, your only real option to safeguarding your data online is, simply, to stay off the internet. This is, for all intents and purposes, an impossibility for the great majority of US citizens whose lives, and livelihoods, have become so dependent on digital technologies.

Of course, the convenience comes at the price of privacy – and there’s really nothing you can do about it – cry ‘fake news’ all you want, but the real news is that, even with increased user scrutiny and awareness about such practices in the wake of the well-publicized Facebook scandals, that we’re still willing to send samples of our DNA to private companies for genetic testing without understanding the legal implications or risks involved shows we’ve still got a long way to go when it comes to doing a better job understanding and advocating for increased data protection.

Even with increased regulation, however, one company that’s got a pretty well documented track record of largely ignoring (or completely disregarding) regulatory scrutiny remains the biggest player in the internet business: Google. The Mountain View based behemoth, whose digital dossier on users includes everything from search history (for optimized ad targeting and personalized results) to detailed, real time location information (via Android or Google apps on other OS instances) to our passwords and payment information (via Google wallet or Chrome’s ubiquitous keychain).

Creepy? Sure. But fulfilling the company’s stated mission of being the single source of all the world’s information includes, inherently, having all the digital dirt on as many people as possible, too – which has proven to be pretty damned good business to date for Alphabet, Google’s parent company and one of the most valuable and profitable companies in the world. At first, Google presented its quest for ostensible omniscience as altruistic, and for years, that seemed to be the case.

However, after losing a record antitrust settlement from the European Commission, to the 1.36 billion rupee fine imposed by the Competition Commission of India for abusing its “dominant position” to engineer “search bias” into its results to the $9 billion in potential GDPR fines the firm racked up the first day the law went into effect for noncompliance (and I could go on with similar suits and pending actions), it’s safe to say that the company has established a corporate ethos of “ask forgiveness, not permission,” seeing data privacy regulations more as a cost of doing business than as a legal mandate they’re required to follow.

Hell, that 1.36 billion rupees, one of the largest civil fines ever rendered by the CCI, works out to about $21 million US, which is to say, chump change for a company valued at half a trillion (that’s trillion, with a ‘T’) dollars. An opportunity cost that’s significantly more opportunity than cost, in other words. These events shouldn’t be seen as outliers, but rather, as the prevailing mandate of Google’s roadmap. In fact, recently the company even officially dropped their famed “Don’t Be Evil” from their corporate code of conduct (and presumably making “Be Evil” acceptable under company policy, by extension).

So, why does any of this matter in recruiting and hiring?

Today, Google announced a significant set of new enhancements and updates to their Google Hire product, including “new AI powered functionality” which promises to optimize and automate many arduous parts of the recruiting process. None of these updates are particularly innovative, nor exciting – they consist mostly of features that are already more or less mainstream within the HR Technology vertical.

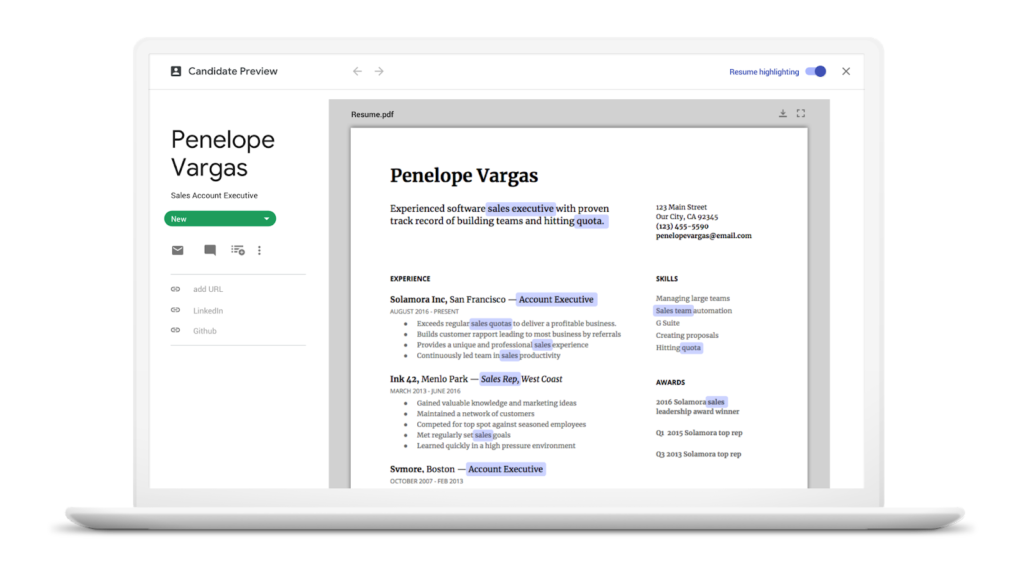

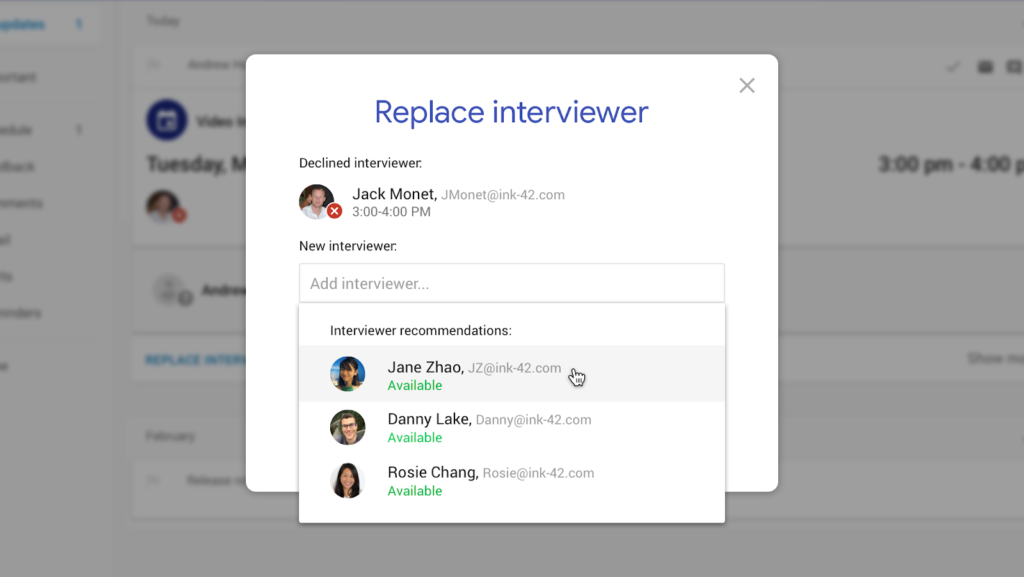

The three most prominent updates being touted by the company in today’s announcement include auto-scheduling interviews based on shared availability, “auto-highlighting resumes” (which is basically keyword matching resumes to job description requirements so recruiters can review resumes even more quickly), and “click to call” candidates, which the company reports will simplify “phone interviews with a one-tap click to call functionality and logs phone calls so team members know who has spoken with a candidate.”

The three most prominent updates being touted by the company in today’s announcement include auto-scheduling interviews based on shared availability, “auto-highlighting resumes” (which is basically keyword matching resumes to job description requirements so recruiters can review resumes even more quickly), and “click to call” candidates, which the company reports will simplify “phone interviews with a one-tap click to call functionality and logs phone calls so team members know who has spoken with a candidate.”

Again, none of these product updates, independently, is particularly innovative nor would normally count as news, save for the fact that it’s HR Tech and anything Google does counts as a big event in an industry where Oracle is the biggest show in town. The real news here is that this marks the first time that the company has reported to “incorporating Google AI” directly into their Hire product.

The implications here run much deeper than the purported efficiencies and process streamlining enabled by these new Google Hire features. As Google notes in their blog post announcing the release:

“There’s a huge opportunity for technology—and AI specifically—to help people work faster and therefore focus on people-centric tasks. Ultimately, that’s what Hire is all about, and the functionality we’re adding today demonstrates our commitment to help companies focus on people and build their best team.”

The ‘huge opportunity’ for AI, obviously, comes with a ton of strings, and Google Hire represents the perfect litmus test for how far, exactly, the privacy paradox extends within recruiting and hiring. In the tradeoff of privacy for convenience, is saving 84% of time on reviewing applications or scheduling interviews really worth sharing proprietary candidate data, calendar information or a complete recruiting related phone log with a company whose entire business is predicated on collecting as many of these kinds of data points as possible?

is saving 84% of time on reviewing applications or scheduling interviews really worth sharing proprietary candidate data?

This is the sort of question employers will increasingly need to answer – and while they are by no means limited to Google, the fact of the matter is that in its current iteration, Hire is uniquely positioned to set a precedent for the future of data privacy in hiring.

Currently, only customers using Google’s Cloud Services can access Hire, which means the platform is almost exclusively limited to small businesses without a ton of enterprise technology or legacy hiring systems, meaning that many regulations such as OFCCP, which would govern the way in which candidate data can be collected and shared, do not apply to smaller companies.

Additionally, Google Hire is only offered in the US, which, as previously mentioned, has the most favorable regulatory environment (or complete lack thereof) around PII and candidate data (as anyone who’s ever done a vanity search and found any sort of surprising and embarrassing result can likely tell you). Finally, Hire is offered as a free add-on for Google Cloud customers as an added incentive and inducement to utilize its service – and that price point, of course, suggests that the business value being created by Google can’t lie exclusively within the Hire platform itself.

The real value, for Google or any other company in the internet economy, is the collection of as much data as possible – and while, again, none of the features announced today are particularly sinister or even cause for concern, the fact that this represents the first “incorporation of Google AI” indicates that the company probably has bigger plans for how it links candidate or aggregate data from Hire into its broader offering of services and solutions.

Obviously, training any algorithm – such as the one required by the skills highlighting feature or the one-click interview optimization – is predicated on collecting tremendous amounts of historical data to improve future results (much like its innocuous automatic suggestions that appear when you’re typing in a search query). There’s nothing inherently wrong, or even malicious, about any of this. Yet.

The fact that Google has positioned this as only the first foray into building Hire into a component of its AI stack signals that they’re actively integrating machine learning and PII-based data into what has been, to date, little more than GSuite with a few modified workflows and basic employer enhancements. But it’s not too much of a stretch to think that within a few releases, things like keyword highlighting on resumes could have been used to train a much more robust AI instance where those same candidates are served targeted AdWords based on their experience or job interests (both obviously rely on keyword matching and object clustering).

For a company that’s got a history of ‘abusing its dominant search position,’ it’s not a stretch to believe that even in aggregate, these capabilities will serve to improve personalized ad targeting (particularly EB and recruiting based campaigns outside the Google Jobs API), serve to provide intelligence on stuff like the likelihood of a candidate to consider a role based on the signals generated by their online browsing history, or even, allow voice-to-apply features that match a candidate’s voice records with their Google Assistant (among dozens of other potential use cases).

Most candidates probably won’t mind. And for employers, the cost and time savings represented by Hire might make moot any such concerns about proprietary or personal data. The problem is, Google isn’t alone in their ability to amalgamate personal and professional information within the same ecosystem and use hiring and candidate data as a way to augment and enhance consumer offerings.

Microsoft’s acquisitions of LinkedIn and GitHub, coupled with MS Office, Azure and Dynamics, prove the power of such a business model, which is why Clippy & Co. were willing to pay such a precious premium for sites that are basically nothing more than repositories of personal data, much of it professionally focused. The value of that data, as we’ve already seen, will extend past those platforms to other products, and that utility will certainly come at a premium price. Nothing stays free forever, as GitHub users will soon discover – but as Google Hire shows, as long as their value extraction outweighs the value-add of these platforms, price is a secondary consideration at best.

Did anyone who shared a code repository or worked on a GitHub project ever think that their work would become the intellectual property of a company whose history is squarely rooted in actively antagonizing and undercutting the open source model of development (see: LINUX)? No, but that’s business.

And in the business of recruiting, there’s no doubt we have to look at products like Google Hire, consider the privacy paradox, and ask ourselves whether or not we’re willing to pay the high cost of free. After all, people might not be your greatest asset and biggest competitive advantage, but the data about them sure is. It’s an investment we should think twice about before expending the capital part of our human capital, at any price point. Period.

Authors

Matt Charney

Matt serves as Chief Content Officer and Global Thought Leadership Head for Allegis Global Solutions and is a partner for RecruitingDaily the industry leading online publication for Recruiting and HR Tech. With a unique background that includes HR, blogging and social media, Matt Charney is a key influencer in recruiting and a self-described “kick-butt marketing and communications professional.”

Recruit Smarter

Weekly news and industry insights delivered straight to your inbox.